Hiking the dunes and lagoons of the remote North East River, Flinders Island, Tas.

Splendid isolation

A new 6-day walk across Tasmania’s windswept Flinders Island is emerging as one of the best multi-day hikes in the country.

STORY ANABEL DEAN | OUTBACK MAGAZINE

It’s the rule of thirds,” Matt Griffiths declares, stooping under branches the colour of bleached bones on the stony flanks of Mt Strzelecki. “It’s an old mountaineering saying that two-thirds of all accidents happen on descent,” he warns, “but I always think that the last third of the mountain takes two-thirds of the effort.”

Comfort has slipped away in an infinite whiteness whipping through trees scrawled tightly around him. The spiny, monolithic peak of Strzelecki – 756m above the southern end of Flinders Island – is dipping in and out of clouds as if dancing through 7 veils.

“We’ve entered into our own little weather system,” Matt shouts into the wind, trying to explain this feral Tasmanian beauty that, literally, takes your breath away. “It’s an orographic cloud that forms as moist air from the ocean hits the tops of the Strzelecki National Park and then condenses into mist.”

Matt’s group has only covered 3km in 3 hours and the dizzying view is entirely absent. There is nothing to see at the summit, no spectacle of sandy beaches scalloped by sea, no sign of the broken chain of Furneaux Islands that lie lumpenly along the horizon towards the Tasmanian mainland.

The hikers scramble on all fours onto humpbacked granite boulders and peer from eyeball-aching white-out into a gauzy abyss. “I love it like this,” Matt enthuses, cheeks gleaming wetly. He’s hallucinating and the infection is contagious. “The only way to cope with Flinders Island fever is to soak it all up and accept that it will stick to you for the rest of your life. Nowhere that I know is like this place.”

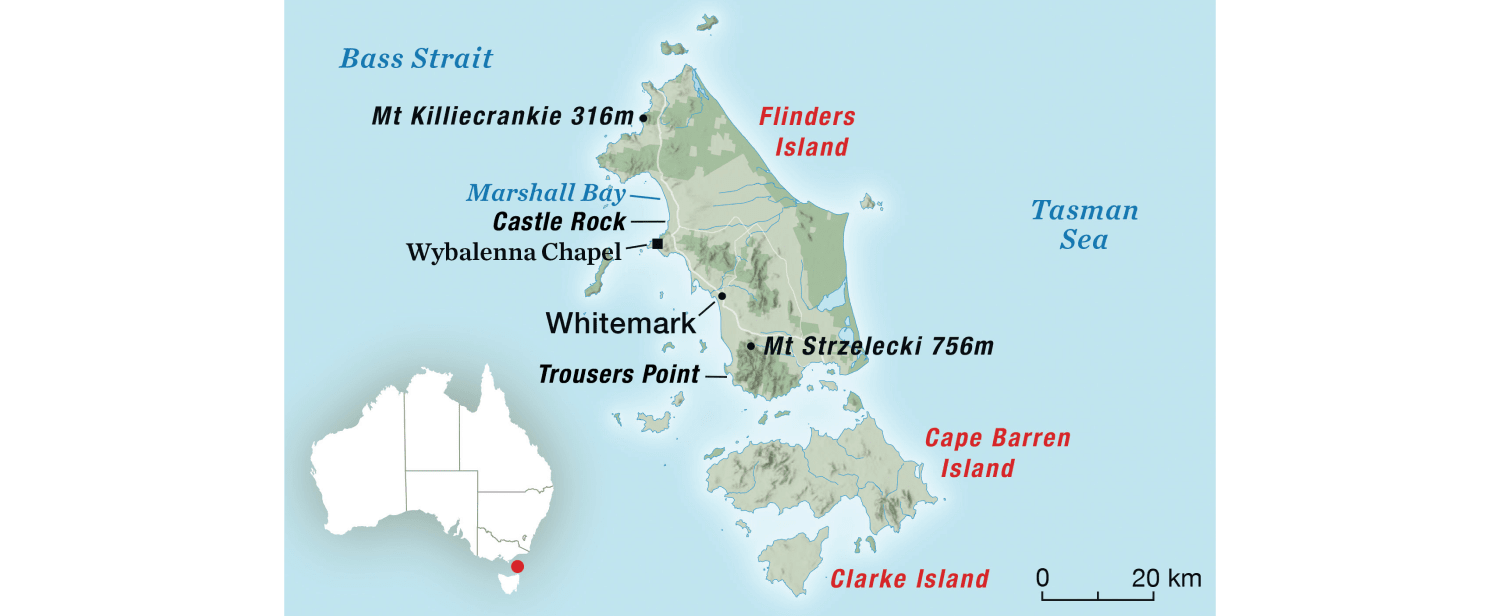

Weather is the governing force in the turbulent Bass Strait where remote Flinders Island lies. It’s the biggest of 52 Furneaux Islands, and 45 minutes by air from Bridport, on the Tasmanian mainland.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Walking from Trousers Point to Mount Strzelecki; Old Mans Head on the Mt Killiecrankie Walk; eco-comfort tent with a view to the stars; Tasmanian Expeditions guide Matt Griffiths; Palana local Hannah Vasiliades.

The island’s untapped beauty has long been appreciated by its 1,000 or so inhabitants, but things are likely to change. The 6-day trek that Matt guides for Tasmanian Expeditions has just been added to the Great Walks of Australia collection of best multi-day hikes in Australia. “I’d probably keep it secret if I could,” Matt confesses.

Mt Strzelecki is just one landmark along a string of walking trails covering 42km of easy to moderate hiking from base camp at Tanners Bay. Flinders Island is small, only 1,333sq km, but weather-dependent off-beaten paths range from rugged Mt Killiecrankie in the north (where gravity-defying boulders balance upon each other) to Trousers Point in the south (where orange lichen carpets rocky coastline).

Isolation has been a catalyst for remarkable biodiversity in this ancient landscape. Matt reckons it’s “like Bay of Fires on steroids”. There is an easy joviality within his company of all sorts from all places: a mathematician, a psychotherapist, a retired teacher and a businesswoman.

Denis Nagle is a keen observer of nature from Gippsland, Vic, who travels alone in the bush for weeks on end. He rises early to watch migratory birds bursting out over pink dawns, hopes to see the endangered 40-spotted pardalote (one of the smallest birds in Australia) or the long-nosed potoroo, and is often the last man on the track, entranced by nature’s marvels.

“Look how this has been bonsaied by the Roaring Forties,” Denis exclaims in the coastal heathlands above Marshall Bay. “In a sheltered area we would walk under this bush, but here it’s been stunted by harsh and relentless salt-laden winds off the ocean.”

Further along the high tide line, the group stumbles upon Castle Rock, a 400-million-year-old granodiorite tor that looks like a 15m high billiard ball potted in the sand. Visitors are alone here, but for a wedge-tailed eagle circling in a cloudless sky above whale bones on a squally shore.

Returning each day to eco-comfort tents pitched like cockle shells in the sand, guides get cracking on camp stoves in the kitchen tent while campers line up for outdoor showers, gas-heated water pumped to a spray head in an open-air cubicle.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Stackys Bight; alpine vegetation towards the top of Mt Strzelecki; historic Wybalenna chapel; Kerryn Alexander summits Mount Killiecrankie; sweet treats in Cate Cook's Tuckshop in Whitemark.

Hunger is speedily satisfied with as much local produce as possible and there is eagerness for a camp bed with a mattress in a tent topped by a clear roof. Can there be a better way to drift to sleep than by gazing at satellites skimming constellations in the southern sky?

At sun up, side flaps unzip to a long-lashed wallaby and the fleeting shadow of a snake in the woodpile. “Don’t worry them and they won’t worry you,” says Matt nonchalantly, flipping a pancake for breakfast.

Another early-rising camper has completed her morning yoga routine. Social researcher Kerryn Alexander is a regular escapee from Melbourne. “I just want to get close to nature,” she offers. “I want to soak in the beauty, the awe of sunset and sunrise, all those stars at night, so I’m glad there’s a chance to be on our own while supported in a small group in a remote place.”

Change of pace comes with a visit to Whitemark. One of 4 small townships on Flinders Island, it has the essentials: hotel, newsagent, supermarket, butcher, baker, cafe, distillery and petrol station. Cate Cook’s Tuckshop, a foodie favourite, is a sure place to meet island residents.

“You don’t live in the Bass Strait to be sociable, but it’s one of the most social places ever,” laughs Hannah Vasiliades, a Palana local. “When you live here, you are part of the community and people are interested in you. Every time you go to the supermarket, you’ll know everybody, so it will take ages to get to the end of an aisle. ‘How’s your hip replacement?’, or ‘Have you preg-tested your cattle yet?’ they’ll ask. They hold the tension until it rains or until they can ship livestock off the island. Everyone is involved in that so you get used to the polite nod because you have to keep going or you’d stop for a half-hour conversation with every single person that you know from everywhere.”

Sandy paths and rock hopping along lichen encrusted granite outcrops at The Docks.

A stark contrast to Whitemark lies on the west coast of the island, where a small red brick chapel sits alone in a paddock. History is heavily loaded at Wybalenna. This is the only remnant of exile for First Nations peoples brought to Flinders Island in one of the most infamous chapters in Australian history. George Augustus Robinson helped to convince the Palawa to escape bloodshed by relocation in the 1830s and ’40s. It was to be a temporary arrangement, with the promise of food, clothing and cultural practice, but ended up being a death sentence, with disease, starvation, wild weather, neglect, despair and estrangement from land and culture.

There’s a field of unmarked graves near a sign that lists the names of 107 Tasmanian Aboriginals who died here between January 1837 and March 1839. Wybalenna was returned to the Palawa community in 1995. It’s a sobering visit with only the sound of wind through she-oak trees. “We don’t like coming here,” Matt confides, “but it’s an important part of the story.”

Time has a way of changing perspectives. Material ambitions drop away in the natural state of grace that comes from simply being here with a resolve to climb a peak, swim a bay or cross a ravine.

“I’m looking over pristine turquoise waters for the last time,” laments Kerryn, standing on the deck of the Furneaux Tavern on the day of departure. A small plane glides over treetops to land on an airstrip in a paddock. The group rallies, pulls up beside the plane and watches the pilot haul luggage into the hold.

“This is an exciting part of the experience,” Kerryn says. “It’s nerve-racking but, in a strange way, I love it. If you could just be here on a whim it wouldn’t be remote or beautiful in the same way.”

The plane takes off, banks steeply and Flinders Island falls away under the wings. There’s a clear view of the known world just up ahead.